Recently, one of our studies was published in the journal New Media & Society. This study examines a crucial and often overlooked topic: the digital participation of low-literate Dutch adults, or those with greater distance from the literate and digital society Our study explores how these people navigate the digital world despite their literacy challenges and barriers and limited digital skills.

Research frame

The Netherlands is considered one of the European leaders in digitalization. However, nearly one in six citizens between the ages of 16 and 65 do not have the literacy level necessary to participate in society, including in digital processes. Because the use of most online technologies requires at least a basic level of language proficiency, a large proportion of these low-literate citizens also lack digital literacy skills. Given the increasing digitalization of society, this means that low-literate adults are at risk of being excluded from society at, simultaneously, the social and digital levels. This leads to large-scale social and digital inequality. While tasks such as filling out a tax form or transferring money through online banking seem mundane, they are highly complex for low-literacy subgroups. This is due to limited language skills and lower levels of digital literacy. Within this context, we examine what social-digital tactics low-literate Dutch citizens use to circumvent their limited functional and/or digital literacy, in order to still be able to participate in an increasingly digitalizing society. With this study, we sought to answer the following research question:

What social-digital tactics do low-literate Dutch citizens use to circumvent their low literacy, and what are the consequences of these tactics for digital participation and their digital inclusion and exclusion in society?

Current perspectives

Previous research has emphasized the importance of a basic level of language proficiency to cultivate digital literacy and participate online. However, a comprehensive and broad understanding of the dynamic and fluid interplay between (low) literacy, digital literacy, participation and its implications for social and digital inequality is still poor. This while implicit assumptions regarding their participation are common, as normative assumptions are present within the abstract concept of participation. Indeed, low-literates within our study were mostly eager to participate, however, in their own designed and situated ways. This research therefore argues for a reconceptualization of participation in light of such disadvantaged groups, taking into account the potential for alternative participatory pathways facilitated by information and communication technologies (ICTs) and external intermediaries. This explains how low-literate populations appropriate participation practices and and develop socio-digital tactics to circumvent their linguistic and digital barriers, and the resulting potential for inclusion or exclusion.

Findings

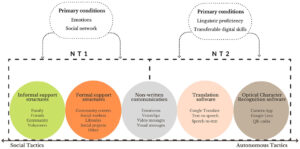

By conducting observations and interviews in various settings, such as libraries, community centers and adult education, we discovered five key tactics used to overcome digital barriers:

1. Informal support structures: Using personal networks for help.

2. Formal support structures: using structured programs and resources.

3. Non-written communication: Emphasis on verbal and visual methods.

4. Translation software: using technology to bridge language gaps.

5. Optical character recognition: Using tools to interpret written content.

The findings show that low-literate Dutch people use a wide variety of tactics to participate in digital society and circumvent their linguistic and digital barriers, depending on different spatial contexts, availability and types of help, capabilities of digital media, and the affective underpinnings of human-technology relationships. Our taxonomy of tactics makes visible the ways in which low-literate Dutch citizens resist strategies and social norms in their own situated ways, and articulates a more social alternation of participation.

Our research highlights the importance of social participation in generating social resources. resources, which in turn facilitate different dimensions of social support. For low-literate NT1 citizens, access to social support structures is crucial for enabling their participatory actions and promoting inclusion. In particular, we observed significant differences in the development and application of digital literacy between the NT1 and NT2 groups. This sheds light on the diversity within these underexposed subgroups. The NT1 subgroup showed a preference for more social tactics, possibly due to their higher average age and lower average education level compared to the NT2 subgroup.

Conversely, respondents in the NT2 group had higher literacy skills in their native language, which led to the development of more diverse digital literacies as they used these skills to compensate for their limited command of Dutch. The lower literacy in Dutch of the NT1 group actually hindered the development of digital literacy. These findings suggest that although digital literacies depend on traditional literacies in specific languages, they can also be partially transferred between languages and sociocultural contexts using ICTs.

The emotional burden of low literacy and digital literacy differs significantly. Seeking help for digital problems can serve as a conduit to address emotionally sensitive questions related to functional literacy. This approach can be used in policy and education to educate low-literate citizens who might otherwise be embarrassed or uninterested in pursuing education. Moreover, we argue that digital inclusion policies do not focus only on individual technical aspects. Instead, it could describe digital literacy as relational, socially situated skills that are nurtured within the context of different actors and sociocultural environments, with the importance of social support structures essential. Moreover, addressing demographic, structural and stratified inequalities requires an intersectional approach to socio-digital inequality. Policies could be designed based on recognition of the interconnectedness of social and and digital inequalities, taking into account linguistic and digital barriers.

These findings counter the stigma surrounding low-literacy groups and reveal their unique and effective ways of interacting with digital technologies. The findings also highlight the diverse capabilities of these people and show their social capital and untapped linguistic potential.

Added value

The added value of this research is threefold: (1) it focuses attention on the capabilities of low-literate citizens that stem from social capital and hidden linguistic potential, (2) it provides visibility into more hidden everyday (digital) practices of marginalized subgroups with greater distance from digital society, and (3) it highlights the lived experiences of users and their (limited) use of ICTs, and how tactics are developed and practiced to circumvent linguistic and/or digital barriers. We argue that digital literacy should not be considered a prerequisite for digital participation and inclusion because our findings show that low-literate Dutch citizens are a very diverse group who are able to participate despite their low (digital) literacy levels. However, they do so in socially situated and more visual ways, in line with their digital and linguistic capabilities and barriers.

We believe this research contributes to understanding digital inclusivity through a human-centered lens, emphasizing that digital literacy is not a strict prerequisite for digital participation. Instead, the research shows the adaptability and resilience of low-literate citizens as they navigate the digital landscape in innovative and socially situated ways.